On Thursday, BuskNY and City Lore will host an evening of songs and stories in a first commemoration of the 1985 case People v Manning, the first to explicitly provide constitutional protection to New York City’s subway performers.

But though Manning was a crucial step forward for performers, it was far from a definitive legalization. The preparation for this program has led us across a trove of documents that reveal a story of legalization more complex and more hard-fought than what is often told. This post will seek to rectify the paucity of information on that era by presenting a few of the performers, activists, and original documents that shaped the period.

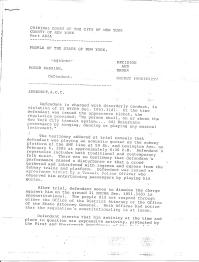

The chapter of subway history most familiar to today’s performers is the 1985 case People v. Manning. In that case, “punk-folk vagabond” guitarist Roger Manning contested tickets he received, in the spring of 1985, under the then-current MTA regulation 1051.3, which forbade riders to “entertain passengers by singing, dancing or playing any musical instrument.”

In the first case where constitutional protection was explicitly granted to subway performance, the court found in his favor, establishing rule 1051.3 as “unconstitutionally violative of the First and Fourteenth Amendments,” relying on NYCLU lawyer Art Eisenberg’s citation of previous First Amendment protection in the 1968 case People v St Clair:

In her decision, Judge Diane Lebedeff notes that the NYCTA “amended its regulation concerning disorderly conduct effective June 14, 1985.” In that amendment, in which the modern-day rule 1050.6 was created, the TA “no longer place[d] a prohibition on any kind of entertainment.” In other words, in the nick of time before the release of the Manning decision, the TA had already removed its explicit restriction on performance.

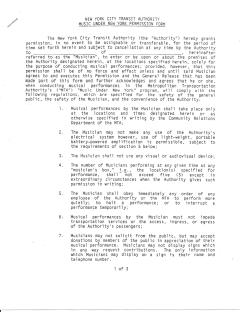

Still, in practical terms, People v. Manning and the accompanying rules change left the subway little safer for most performers. Summonses continued to be written, not only on pretexts like blocking traffic, but also under the new 1050.6(b) ban on “solicit[ing] money for goods, services or entertainment.” Although performers accepted donations rather than soliciting them, this nuance was lost on MTA agents — and on police as well.

Worse, the MTA attempted to describe membership in the new program Music Under New York as a legal requirement:

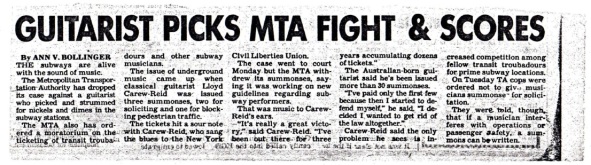

Enter Lloyd Carew-Reid, an Australian-born classical guitarist who chose to contest the MTA’s summonses. Carew-Reid’s fight stuck, both legally and in the public eye. Ultimately, the MTA was forced, according to a January 30, 1987 AP article, “to put a moratorium on issuing summonses” to subway performers. (Later, in 1989, it would issue the new rule 1050.6(c), recently publicized during the arrest of Andrew Kalleen, which for the first time explicitly stated that “artistic performance, including the acceptance of donations” was permitted).

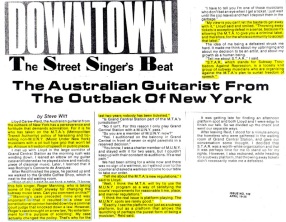

For this reason, Carew-Reid argued in performer and journalist Stephen Witt’s long-running column The Street Singer’s Beat circa 1989, “Roger [Manning]’s case [only] brought on a new law, ‘No entertainment for the purpose of soliciting’. My case actually changed the policy. That’s why for the last two years, nobody has been ticketed.” In a word, then, 1987 saw the practical legalization of performance as the MTA ceased to systematically issue tickets; 1989 would then see explicit allowance of busking, under 1050.6 (c).

Carew-Reid and his advocacy organization, Subway Troubadours Against Repression (STAR), went on, in a historical series of public hearings, to successfully fight a proposed rules change banning performance on platforms. STAR also fought a ban on amplifiers on the platforms, arguing that the rights of those performers whose genres inherently involve amplification were being violated. (This argument resulted in a stay against the amplifier ban by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, but was ultimately rejected. Amplifiers remain banned on the platform, but are permitted on the mezzanine level).

Following STAR’s lengthy fight to protect performers, the gap was filled, in the late 1990s, by the Street Performers Advocacy Project, which emerged from the pioneering academic work of Susie Tanenbaum. SPAP produced a written pamphlet to advise performers of their rights, and informed countless more through a widely-cited online resource, the Know Your Rights guide.

Still, despite these decades of advocacy, the safety of subway performers remains precarious. Due to inaccurate media coverage of Music Under New York auditions, which erroneously suggest MUNY membership to be a legal requirement or “permit,” performers continue to be wrongfully ejected, ticketed, and even arrested.

As one such arrestee, I have channeled my experience into co-founding BuskNY, which has spoken out for threatened performers. Others, including Erik Meier and Andrew Kalleen, have spoken out, with Kalleen’s video alone reaching 1.5 million viewers online.

The most recent chapter of subway performance history has thus seen greater attention brought to the legality of performance — and, we hope, a move toward the definitive end of the oppression fought by Manning, Carew-Reid, STAR, SPAP, and many more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.